This guide is available along with a detailed appendix on the app’s options and settings (1・2) on Apple Books (free):

The apps recommended in this guide are only available for iPhone and iPad.

Almost anyone can appreciate the aesthetic appeal of Japanese calligraphy.

But, if you’re studying the Japanese language, kanji can also be terrifying.

Thousands of seemingly random combinations of lines; how will you ever remember them all?

Well, they aren’t random. Kanji is a writing system that has been developed and refined over thousands of years in China and further refined by the Japanese when they imported it to their language.

Because the kanji are systematic in nature, you should study them in a systematic manner.

This guide is for the upper beginner to lower intermediate student of Japanese. You should already know some Japanese words. You probably already know a few kanji. Perhaps you’ve already forgotten a lot of the kanji that you studied in the past.

I’m gonna show you how to stop forgetting and study kanji the easy way.

If you’re even a just a casual student of Japanese, you’ve probably heard of using mnemonics and SRS to help you study kanji. That’s basically what this system is as well.

So, the system itself isn’t new but my implementation uses your iPhone to help you manage your studies and relies on studying in a contextual manner. What I mean by context is that you really shouldn’t just be studying kanji by themselves. Kanji is a system used for conveying ideas and so I think it’s better if you study them within the context of conveying ideas.

This method uses an app called kanji Flow which makes it very easy to study with context because it features a built-in examples database. It will automatically show you the most common words for each kanji and example sentences for most Japanese words.

This study system won’t work for everyone, but if you already have at least some knowledge of Japanese and you can devote 25 minutes a day for 30 days, you’ll study 300 kanji and be well on your way to 1000, 2000, even 3000 characters…much more than the average Japanese person.

If you’re not familiar with using mnemonics to study kanji, basically you will break kanji down into smaller, less complex pieces, and create your own, personalized reading system in order to help you try to remember what they look like. When I say reading system, I actually mean stories. You’ll be reading the kanji by making up a story based on what it looks like. You’ve probably already naturally done this as you’ve been studying. I’m gonna help you make that more systematic and ensure that every new kanji you study builds upon what you’ve studied in the past.

With kanji Flow, you’ll study the characters as they are used in words and sentences and not just by themselves in order to really understand what they mean and how to use them. And kanji Flow’s SRS will manage your study schedule automatically so there will be no wasted time trying to figure out what to study when.

The Secret

Let me be clear right from the start that this method is not magical. There is no effortless way to study kanji.

There is no miraculous method to being good at anything. Whether it be baseball, piano, or Japanese; if you want to be good at something, you already know exactly how to do it:

Work.

It will take time, energy, and effort to study Japanese and kanji. Quite a lot of all three, in fact.

However, there are certainly more and less efficient systems and methods available to you.

This method simply aims to be more efficient.

This method also aims to be cost effective. The necessary book has a free sample version available on the web and that’s all we’ll need. Both of the iPhone apps I’m going to suggest are free to download. Neither of them have ads or in-app purchases. I’m also going to recommend a website which is completely free to use as well, although you will have to create an account.

If you don’t use an iPhone, I’m sure there must be similar apps on Android and Windows Phone but you’ll have to research what’s available and learn to use them yourself. Also, they probably won’t integrate together the way the iPhone apps do but, at worst, that’ll just mean a bit of extra work on your part.

Anyway, let’s go over the basics and see how this method works.

The Basics

We’re going to be using Remembering the Kanji by James W. Heisig.

While it wouldn’t hurt to actually buy the book, (and I suppose I should encourage you to in appreciation of Mr. Heisig’s work) you’ll actually only need to use the free sample edition:

Remembering the Kanji Sample, 6th Edition

Save a local copy of the PDF so you’ll have quick access to it later if necessary…it’ll probably be necessary.

It would be best for you to read the entire introduction in order to get the best understanding of how this method works.

It is a bit long though.

You should at least read:

- Forgetting Kanji, Remembering Kanji

- The Structure of this Book

- Admonitions

If you don’t feel like reading it all now, that’s okay. I’ll summarize it for you and you can go back and read the original if you happen to run into any trouble or just want to get a better understanding at a later point:

- There are too many kanji and they are too complex to study using visual memory alone — that is, simply trying to remember what each one looks like.

- Instead, we should use imaginative memory — we should make up and associate an idea (or a story) with each kanji and remember the ideas — which should, in turn, help us to remember the characters we’ve associated with them.

- The ideas will be wholly personal to you and, thus, easier for you to remember

- At first, we’ll take the simplest forms (single lines, pairs of lines, boxes, etc.) and associate these primitive shapes (which we’ll call primitives from here on out) with simple ideas.

- Primitives might be single strokes, radicals, or even complete kanji that appear as a part of other kanji.

- We will combine these primitives into slightly more complex kanji and associate slightly more complex stories with them.

- We will continue on in this way, creating ever more complex stories and building up an ever more complex lexicon of characters we know.

- No special effort will need to be made to actually study the primitives; remembering them will occur naturally by simply using the primitive shapes as you study each day.

- Each primitive and kanji will be assigned a keyword that can be used when creating your stories.

- Kanji will be studied in the order that is most efficient for studying.

Got that? If not, just bite the bullet and read through the actual introduction yourself.

You’ll note that in the introduction, Mr. Heisig specifically states that one should NOT worry about trying to read kanji (that is, one should NOT do the type of contextual study -reviewing words- that we’re going to do) and should focus only on understanding how to write them. I think that only goes for students brand new to studying Japanese. If you are brand new, stop reading this, buy his book and do it the way he says. It’s better. This method is for those that have already been studying Japanese for a while, already know some Japanese words, perhaps even already studied a few hundred kanji but forgot them and/or don’t know a good, systematic method for studying them. With this method, you’ll be associating words that you already know with the kanji you are studying as you practice reading and/or writing them. I believe doing so can help to reinforce kanji studies for the upper beginner to lower intermediate student of Japanese.

I think it may still not be quite clear at this point what exactly we’re going to be doing so let’s take a look at a simple example and go through it step-by-step.

Kanji Koohii

We’ll start out with what should be an easy kanji for most upper beginner or lower intermediate students. If you don’t know it yet, that’s okay, we’ll study it together.

安 (アン) is a third-grade character (according to the Jōyō system) and comes in on Heisig’s list at #202. It’s used in words such as 安全 (あんぜん) — safety, 安定 (あんてい) — stability, and 安い (や.すい) — cheap. If you look it up in a kanji dictionary you’ll find various meanings listed such as: relax, cheap, low (as in price), quiet, rested, contented, and peaceful. I think most people think of this kanji as meaning cheap because of the very common adjective it’s used to write (安い) or something like relax or peace because of the common nouns it’s used in (such as 安全).

This kanji is composed of two parts: 宀 and 女. The second part is easiest: 女 is the kanji for woman. So, of course, the keyword we’ll use for this part of the kanji is woman.

The first part, 宀, is called うかんむり in Japanese. かんむり (冠) means “crown” in Japanese and I guess they imagine the shape is somewhat similar to the katakana ウ, thus う・かんむり. In English, this part is usually called the roof radical and in Heisig’s system it’s known as the roof primitive. So, the keyword for this part is roof. Roof gives us a lot of freedom when using it to make up stories. We could also imagine that anything that is under the roof is also at home or in the house.

This kanji’s keyword in Heisig’s book is relax. So, we need to make up a story using the keywords of the two parts that make up this kanji, woman and roof (or at home, in the house) that also makes us think of relax:

a Woman RELAXing At Home

Simple enough but perhaps too simple and, thus, easy to forget. Hmm…how about:

stay-At-Home Women just RELAX all day

A bit sexist. That’s good…I mean…no, that’s bad, of course, but it is good for remembering. Slightly weird or controversial or bad or funny or erotic things are easier to remember than simple or normal things. Whatever works best for you is okay. Also, notice that I currently like to capitalize component keywords and put the kanji’s keyword itself in all caps. You don’t have to do that, of course. It’s just the way I like to do it.

So as long as we know what woman and roof look like, we should be able to easily visualize what this kanji looks like and what it means by simply thinking about this silly little story.

I realize that I’m making the assumption that you’ve already studied woman and roof. Well, what if you haven’t already studied them? You should just be using these basic shapes and primitives almost every day as you study. Roof looks like a roof and woman looks like a pregnant woman. And, these parts are used so often in the other kanji that you’re going to be studying every day that you should be able to just remember them out of necessity with no special effort required.

But, wait a second! Everybody knows this kanji actually does mean cheap, and not relax. So, why did Heisig decide to call it relax? Well, keep in mind that these stories build up over time so he may have wished to use it in the story for another kanji later and he felt that relax worked better than cheap.

Anyway, if you really disagree with a keyword, feel free to change it. This is supposed to be wholly personal to you, right? Okay, so now we need to make up a story with roof and woman that makes you think of cheap… Hmm…I can’t think of anything. That’s okay, the internet will help us.

Kanji Koohii is a database of kanji stories that you can use for inspiration when you’re having trouble coming up with a story.

An account is required to use it. The info you have to provide is minimal, however, and the wealth of data you get access to in return is amazing so get to signing up.

Once you’ve done that and logged in, go to Study and then Browse. To see some stories for 安 you can search for the character itself, type in the keyword (relax), or just use Heisig’s number (202). All three of those things also work as a direct URL: http://kanji.koohii.com/study/kanji/(insert query here)

http://kanji.koohii.com/study/kanji/%E5%AE%89

http://kanji.koohii.com/study/kanji/relax

http://kanji.koohii.com/study/kanji/202

You’ll notice that there are lots of stories here that are fairly similar to the one I came up with as well as some stories from people that insisted on changing the keyword to cheap. There are even some stories that use both keywords such as this one from user Yojax:

the CHEAPest place to RELAX with a Woman is At Home

Actually, I think I like this story better than my own so this is the one I’m gonna use.

Now let’s take a look at a slightly more complicated example:

This is an 8th grade kanji and is #308 on Heisig’s list. The keyword is metaphor and that’s what the kanji itself means as well. It’s only used in one common word: 比喩 (ひゆ) which means… metaphor.

Again, we have a kanji composed of two parts. The first part is 口 (mouth) but what’s that second part? Well, if you check the Kanji Koohii site, you’ll see rather quickly that most people seem to be calling it a meeting of butchers. Why? What the heck does that mean? If you’re confused, it’s a good bet that someone else was too.

Try reading through all of the stories and you’ll probably find one that explains it. If not, head back to the kanji immediately preceding this one (just use the little back button in the browse section in the upper left) and see if anything is mentioned in their stories. Chances are, you’ll be able to figure it out by just using the website and not actually need to check Heisig’s book.

This part seems to be called a meeting of butchers because the top part looks kind of like a tent with a table, similar to the meeting kanji: 会. Butcher comes from the flesh radical (月 — which you may notice is actually the moon but is also used in all of the kanji for body parts) and the saber primitive (similar to 刀 — sword). However, if you look closely, you’ll notice that it’s not the normal saber primitive. The lines are bent and it actually looks like the flood primitive, similar to the く hiragana. Basically, it seems that the normal saber is usually used in the Chinese version of this character but the Japanese version seems to normally be written with the flood primitive. I think this is the only kanji that uses this particular combination of shapes so you’ll notice that some people give this a special keyword and call it the koo-koo butchers because of the くく. So, this one is quite complicated. But don’t worry, this is a rare case; most of them won’t be this difficult.

An interesting thing about this kanji is that a lot of Japanese people don’t know it. You probably don’t really need to know it either. So why should you waste time studying a pretty useless kanji, especially so early during our studies?

Well, remember, I said that kanji would be studied in the order that is most efficient and this one fits in here due to the kanji that come before and after it.

If you feel that a certain kanji is so useless that you don’t need to remember it, feel free not to. If it happens to come up in another kanji later, you can try studying it again at that time.

Another point to mention while we’re talking about “useless” kanji: you’re gonna get some name kanji (characters that are generally only used in names) that are really only useful as pieces to help you study more complicated kanji later down the road. I usually try to find a famous person or place to associate with the kanji to help remind me it’s a name kanji. You can feel free to do that, or just not worry about them too much.

Again, this is supposed to be personal to you so you can basically do whatever you think is best as you go along.

Hopefully by now you have a pretty good idea of how the method works. Now we need to get organized.

The Apps

So far, all that’s been discussed is the way kanji characters look. But what about readings? What about studying vocabulary? What about actually understanding how to use these kanji? And how are we going to manage our studies day-to-day?

That’s what the apps are for.

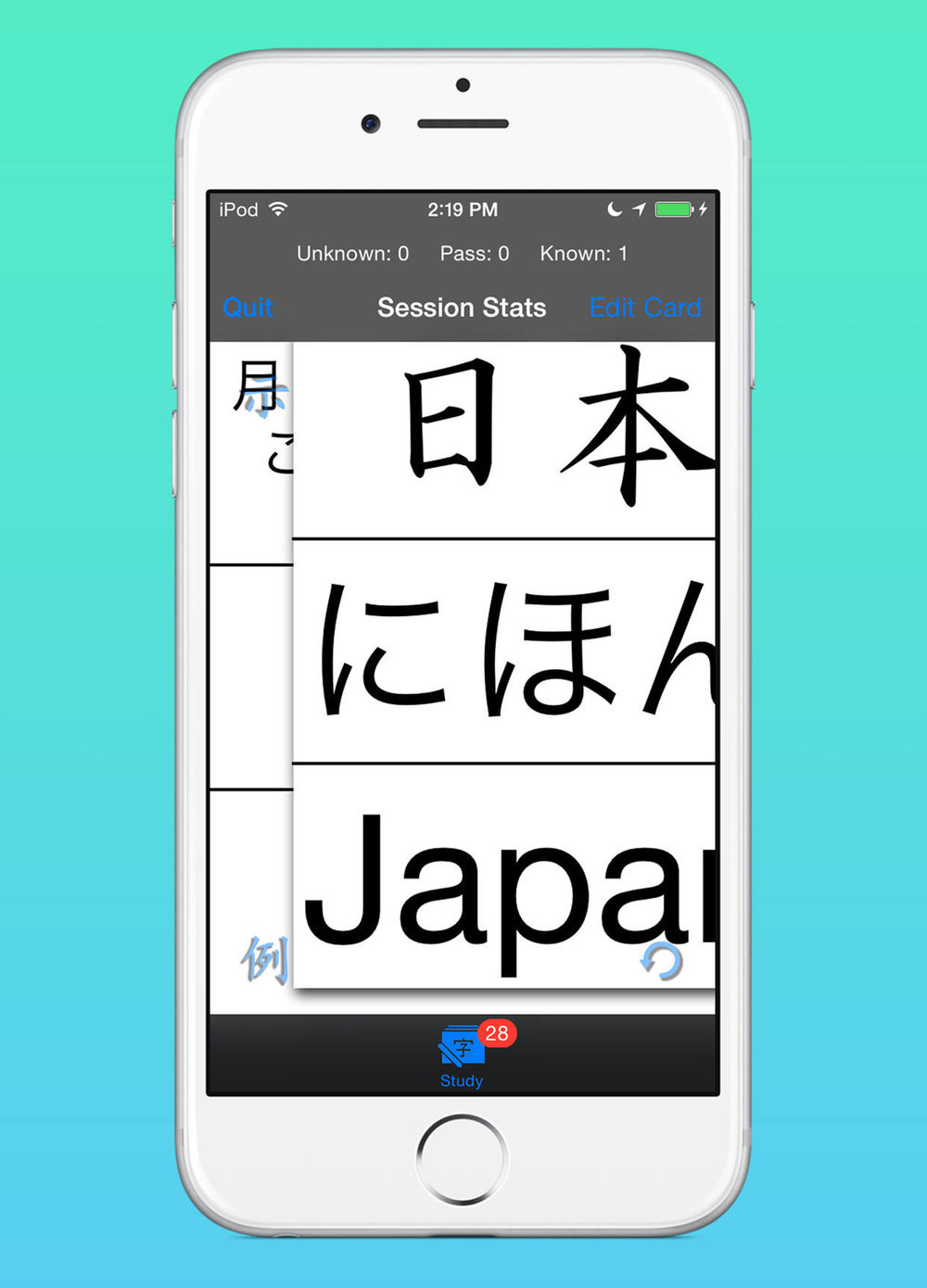

So get your phone out and search the App Store for kanji Flow and download it. I think it isn’t that big so it should download pretty quickly.

When it’s finished launch it and (if it’s not already on your phone) you’ll get a prompt to download imiwa? Do so.

imiwa? is a dictionary and, thus, fairly large so it’ll take a minute or two to download. While that’s happening, let’s talk about what kanji Flow and imiwa? are.

imiwa? is easier, so we’ll start there.

imiwa?

imiwa? is a multi-language Japanese dictionary based on the JMDict Project by Jim Breen. Basically, the JMDict is a user-curated database of Japanese words associated with their appropriate equivalents in a several European languages.

imiwa? is going to help us in a few different ways. First of all, it’s a dictionary so, duh, you’ll use it to look stuff up. You’ll use it when you want to remind yourself of a kanji’s stroke order (we’re going to talk more about stroke order later, too). You’ll use it to get at a complete list of compound words for each kanji you study, if desired. You’ll use it because it’s directly integrated with kanji Flow and it will save you a TON of time typing and/or copy and pasting. imiwa? is awesome and has way more features than mentioned here. Check it out on the web for more info:

The creator of the app, Pierre-Phi, and his partner in crime, Francios, are both wonderful gentleman and work on the app in their spare time. If you appreciate their work, it wouldn’t hurt to toss them a couple of bucks via the homepage’s donate button.

As for kanji Flow, it’s a flash card application but…actually it’s a bit more complicated than that. It’s an SRS app.

SRS — How NOT to Forget

SRS stands for spaced repetition system.

It is used to not forget things.

Basically, if you don’t want to forget something (in our case, kanji characters), you should review it and remind yourself of it just before you’re about to forget.

Too late and it’s already forgotten. To early and you’re being inefficient.

The more times you are reminded, the better you should know it, and the more days you can wait before you need to review again.

Actually, that’s pretty much it.

However, managing such a system yourself can be a bit difficult. Can you imagine if you had 300 physical flashcards and had to remember how many times you used each one as well as calculating when you should review each card again every time you studied it?

Managing the SRS would be more time-consuming than the studying itself so, of course, we should use software for that.

kanji Flow is an iOS SRS app and is great for our purposes a few reasons.

First and foremost, kanji Flow is integrated with imiwa? which means you can create new cards instantly by simply tapping an export button and then an import button. No typing. No copying and pasting. No time wasted making new cards. (You aren’t going to have to make any new cards anyway since I already made complete decks for you).

Secondly, kanji Flow has a built-in example database. It’s going to automatically show you the most common words for any kanji you study or example sentences for (most) words that you study. The contextual study component of this method is available automatically with no extra work required on your part.

Finally, kanji Flow has direct links to search the website (Kanji Koohii) we’re going to be using for story inspirations so you won’t even have to waste time switching to your web browser and doing the search manually.

Again, this method aims to be efficient. I don’t want you using up all of your time making flashcards or tweaking software. You’ll spend about 25 minutes a day studying kanji, and that’s it.

For those that are interested in the details, kanji Flow and Anki both use the same SM2 algorithm to manage study intervals. The individual implementations are slightly different, of course, but, over time, there won’t be a dramatic difference in how the two would manage your studies.

Let’s get into kanji Flow and learn how to use it.

kanji Flow

kanji Flow can be found at the following locations on the web:

kanji Flow can be a bit confusing the first time you look at it, especially if you haven’t used SRS software before, but it’s actually quite easy to use. We’ll go through a quick tutorial together and then we’ll dive right into actually studying some kanji.

How to Study

Now, let’s talk about how you’ll actually be using kanji Flow to study every day. I’m gonna give you my basic recommendations for studying and then, as you grow more accustomed to it, you can, of course, start doing things your own way.

I’ll try to make videos for the more complicated stuff just in case you need to see a walk through.

We need to change a couple of settings before we start.

Go back to your home screen and then load the Settings app. Scroll down and find kanji Flow near the bottom and select it.

Under Max Cards, slide the slider all the way to the left. This means that our maximum number of cards for Flow study sessions won’t be limited.

Scroll down and turn Write Examples First under Contextual Study off. This will allow us to study in a more systematic manner.

When you’re done with Settings, head back to the app.

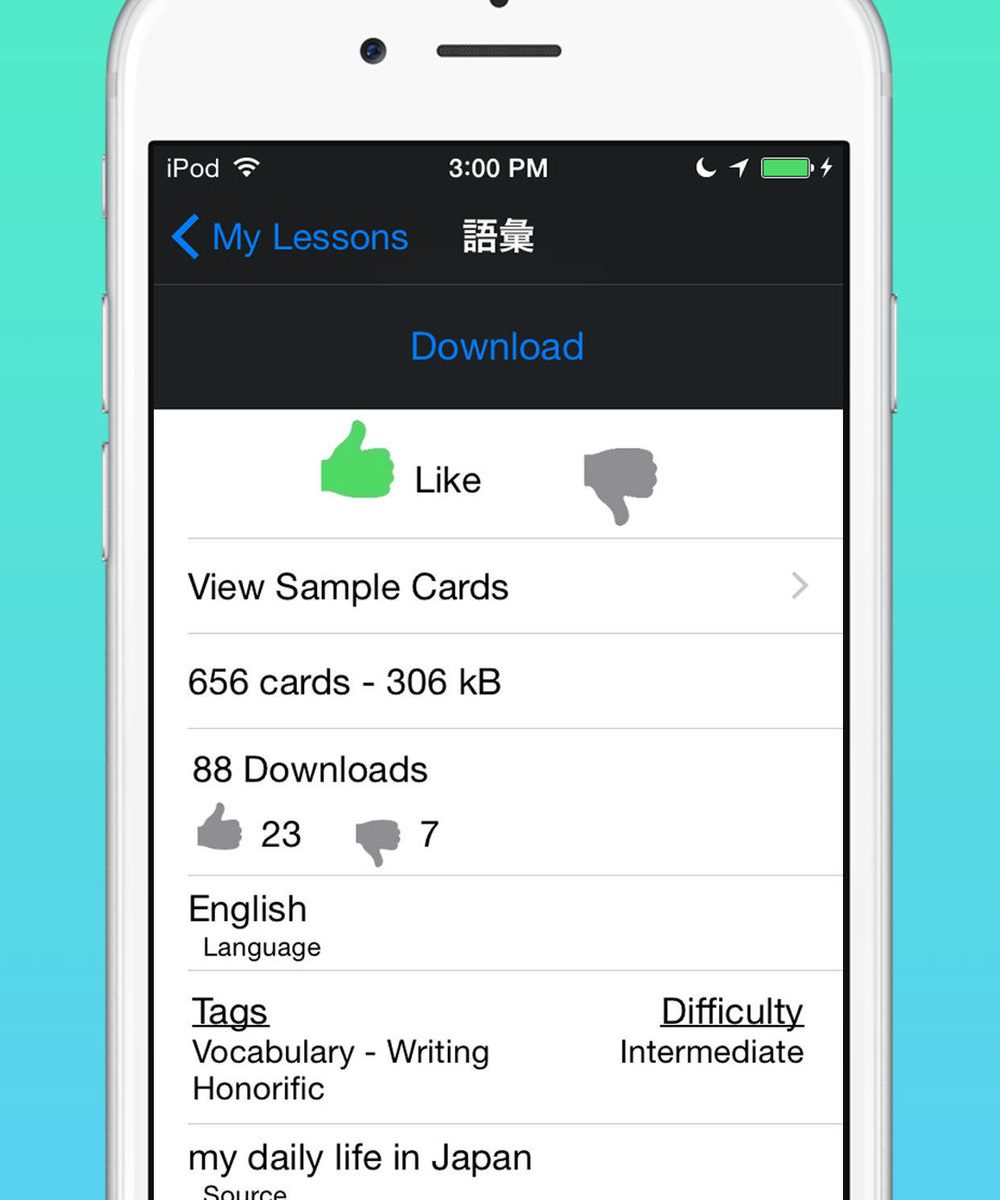

Shared Lessons

In the Getting Started video we weren’t using a real Japanese lesson so I think it might’ve been difficult to see how the app really works. So, let’s get a real lesson with actual kanji and use it to learn how to study.

Tap Lesson List and then select Shared Lessons (you’ll need to be connected to the internet for this to work). Go to the search bar and search for Remembering… for now we just want to get the intro lesson so tap on that one and then tap Download. Once that’s complete, you can head back to the Lesson List and then tap on the lesson to open it.

Study Sessions

First of all, let’s make a quick change in options. Tap Options and set Kana Style to w/Kanji. This will make the card’s Kana entry and Kanji Entry appear together with only one tap. This might sound a bit confusing now but it’ll make sense once we actually start studying.

Tap Study. You’ll notice that you’re only getting 10 new cards in the Flow option. I think 10 new cards a day is a good amount when you’re starting out. If you’re an upper beginner or lower intermediate level Japanese user, you’ll probably already know a lot of the kanji that you’re going to be seeing anyway so it really shouldn’t be too much of a burden.

Once you really get going, I think 10 a day might be too much. I personally do 4 new kanji a day. I’m usually pretty busy on weekends so, while I definitely review the kanji I’ve already studied every day, (and you have to as well) I only add new kanji 5 days a week. That’s about 1000 characters a year. Efficient enough for me and not at all stressful. My study sessions only take about 25 minutes a day even though I currently have about 1200 characters in my active study list.

I’ve heard that some people do as many as 100 new kanji a day. That’s great if you can do it but what’s the rush? It must be really stressful. I think it’s best to keep it simple and easy so that you don’t get fatigued.

You should never feel fatigue or pain or any other kind negative feelings when you’re learning to do something. Pain and negativity will cause you to give up. You should always finish thinking, “I could do more than that.” And you will…tomorrow.

Keywords

Anyway, go ahead and select Flow. The first thing you’re going to see is a keyword. There should be one keyword associated with each kanji that you study. You will use these keywords as the components of the stories you’re going to create in order to visualize what the kanji look like. I have put in all of the default keywords for each kanji from the Remembering the Kanji book.

Sometimes, you’re going to disagree with the keyword. You’re going to think, “Well, yeah, this kanji is for mouth but the meaning is actually something more like orifice or opening.” Okay, fine. Change it. Tap Edit and then change it to whatever you want (just be sure to tap Save). It’s also totally fine to associate more than one keyword with a kanji if necessary (and you will be doing this for some of the more common primitives) but the key is to not let things get too complicated.

Try to keep it simple.

Mechanical Studying

Okay, so, how do you actually study new kanji? This is how I do it. I see the keyword and I say it out loud. If you’re on the bus or in a cafe and can’t speak out loud, that’s okay; just actively say it to yourself in your head. Tap the top section on the right half of the screen (tapping the left side will move you backwards through a card’s examples and tapping the right side moves you forward) and it’ll move on to the story for this kanji. Read the story out loud. The story for mouth is really simple because the kanji is really simple. Things will get a bit more complicated as we go on.

Tap the center or bottom section and the card’s readings and the kanji will appear. Write the kanji down (yeah, you should have a pen and paper when you’re studying). As you write the kanji, say the story to yourself. If you don’t have a pen and paper handy or if you’re on the bus or something, just use your finger to write the kanji on the palm of your hand. Or at the very least, go through the mental process of imagining yourself writing each stroke in your head. What if you don’t know the correct stroke order? Tap the center again and then select imiwa?

Whoops…you might not get the kanji. Okay, let’s change a few imiwa? settings to make sure it’s working the way we need it to.

imiwa? Options

Open the hamburger menu (the three lines in the upper left) and then tap the gear for settings. Turn off any languages that you don’t need. I recommend turning off Auto search clipboard because it can be a bit annoying if you use the pasteboard a lot like I do. Turn on Recent at top (lists). And turn on Inline kanjis. Turn off all of the romaji; you don’t need it and if you think you do, then please stop. You really shouldn’t be using romaji if you’re serious about mastering kanji. I also recommend turning off any of the Readings, Character Sets, Look-up Codes, and References that you don’t need just to keep things cleaner.

Okay, then tap done. Go back to the dictionary. Tap the search bar and then search again (the kanji you searched for will be at the top of the recent searches list). Now we’ll get the kanji entry at the top. Select it and you’ll get to see the stroke order for the kanji.

If you’re having trouble with stroke order, check out Tofugu’s guide on the subject. Stroke order, like the characters themselves, are systematic. Just try to understand the system and you’ll find yourself having to worry about proper stroke order a lot less. You’ll probably still need to check sometimes, though.

Write it down.

If it’s a complicated kanji and you feel like you need to, you can go ahead and write it a couple of times or 5 or 10 times. Whatever you feel like is necessary for you. If you really don’t feel like writing kanji no matter what, that’s okay and it’s totally up to you. However, I really recommend that you do it. I know that you don’t need to be able to write kanji these days but I feel like the mechanical activity of actually writing the kanji will help you to internalize it more quickly. Mouth is really easy but things are going to get more complicated rather quickly and we want to build good study habits right from the start, so get to writing. When you’re done, go back to kanji Flow.

Tap the top section again (on the right half of the screen) and it’ll show you an example word. If you don’t know what the example means tap the hint button to get the translation. Don’t worry about trying to study new words or trying to double-up your kanji studies with studying vocabulary…don’t try to memorize the example. Just look at the word and understand that this kanji is used to write it. Say the example word.

Say it out loud.

If you think your pronunciation isn’t good, long press on the word and then select Speak. Listen to and repeat the word as many times as necessary. This is a computer-generated voice but you can still get a better idea of how to say the word, in general. Tap done when you’re good to go. Tap again to get the next example word. Say it. Rinse. Repeat.

You only need to do this mechanical, active study style when you’re studying completely new kanji. Once you’ve become pretty familiar with the character, it’s enough to just go through the process of recalling the kanji. If you’re confident that you know a kanji very well, just recall it and then swipe it right. If you’re not quite so confident, re-read the story, write the character down while thinking about the story and each component, and then maybe look over a couple of examples.

I tried to put in common examples that include each of the kanji’s different readings. If there’s a common verb or adjective associated with the kanji, that’ll usually be an example as well. Go through the examples like this until you get back to the keyword. Say it again.

If you think you understand this kanji, no problems, swipe it right. If you aren’t sure, swipe it up and try it again tomorrow. If you think this kanji is kind of difficult and you don’t really know it, swipe it left. I think mouth is pretty easy so I’m gonna swipe it right.

Kanji Stories and Using Kanji Koohii

Hmm…now let’s say you don’t like a story. You need to like it. The story needs to be interesting to you so that it’s easy for you to remember. If it’s not interesting, make up a different story. Some people like to make up stories associated with something they know a lot about like baseball, music, or computer programming. Some people like to make up funny stories. Some people like to only use erotic stories. Whatever works for you is what you should use. I just put in possibilities for each kanji. If you know that you don’t like the example story I put in for but you also can’t come up with anything interesting yourself, let’s get some inspiration. Tap the center again to get the alert menu you used to open imiwa? but this time select Kanji Koohii.

The first time you select this you’ll need to sign-in or create an account if you don’t already have one. Once you create an account and sign-in (make sure you select Keep me logged in) you should stay signed in for good unless you do something like reset your device or reinstall the app. Tap done and then tap the center again and this time when you tap Kanji Koohii, you’ll actually get some results.

You’ll see a lot of stories from other users that you can copy or simply use to inspire a story you create yourself. If you like a story, long press to copy it. Once you’ve got the story you like copied, tap done to go back to kanji Flow and then tap the Example button in the lower left and then tap import. Once you’ve got your new story in there, tap edit to slide the story up to the top, then delete the other one and tap done.

The Remembering the Kanji Intro lesson has an example story for all 294 cards. Once you transition to the real, 3000 card lesson you’ll have to come up with your own stories so it’s a good idea to get used to using Kanji Koohii and adding stories now.

Now just keep going through your cards, actively thinking about the keyword, story, components, and example words…speaking of examples…what if you don’t like the ones I chose? What if there’s a word that you closely associate with a kanji because you use it or run into it a lot? You should definitely be using that word instead of the ones I chose. Remember, this should be personal and customized to make it as easy as possible for you to study these characters.

Adding Examples

Tap the Example button in the lower left and scroll down. You can add the examples from the database into your examples list by just tapping on them. Generally speaking, you’ll find up to 8 common words for each kanji in the database. The commonality for these words is based partly from a corpus of Japanese newspapers so there might be some newspaper words that actually aren’t so common in everyday-spoken language, so do be a bit careful.

If the kanji isn’t so widely used, there may be some words here that really aren’t so common or that are actually usually only written using hiragana. And if the kanji is really quite rare, there might not be any words at all. When you run into kanji like this, you’ll usually find out that there probably is some use for it. It’s used in some very specialized word like the name of an era in Japanese history or it’s used to write a place name or it’s used in a person’s name. If you want to, you can hop on Google or Wikipedia and try to find something that you can use as an example. You can do a Google Image search from the same menu you access imiwa? and Kanji Koohii from, if you’re interested. If you don’t care, you can just leave it without any examples and that’ll tell you this kanji is just being used as a component or primitive. It’s entirely up to you.

If you don’t like any of the examples in the database then you can open up imiwa? and see if you can find some better examples there. If you find a word or two that you like or are more familiar with, you can tap on the word and, after opening the export menu using the share button in the upper right, tap Copy for the first word you like and then Copy and Add for any subsequent words. Head back to kanji Flow and tap Import. Delete any of the default examples that you didn’t like. I think I put in examples for about the first 50 kanji or so…after that, you’ll have to get your own examples. Remember, just tap to add them from the database on the examples menu or copy some from the imiwa? dictionary.

I recommend that you only have a couple of examples for each word so that you aren’t spending too much time going through them as you study. Again, don’t try to use this as a way to study new vocabulary. Our focus here is the kanji. You can worry about studying new words after you’ve mastered the writing system.

Transitioning

Once you’ve done your 30 days and studied the 294 kanji (yah, I cheated, “294 Kanji in 29 and a Half Days” just isn’t as catchy) in the intro lesson, you’ll need to transition over to using the full Remembering the Kanji lesson that’s available from the Shared Lessons menu. Go ahead and download that one and then let’s talk about how to get your cards transferred.

In your intro lesson, with all 294 cards selected, head to the Edit screen and then tap Export Cards. Tap the Cards to Pasteboard button at the top of the list. Go back to your Lesson List and select the new, full Remembering the Kanji lesson. Go to the Edit screen again but this time tap Import Cards. You’ll get a warning that the cards are all duplicates but don’t worry about that, choose Import Anyway. Next, tap Duplicates in the upper right…it’ll take a bit of time to process since it’s looking through a lot of cards. When you get the choice, choose Keep Newest Cards. That’ll delete all of the fresh copies of the cards you’ve already been using and just leave your old cards in their place.

Now, you can just go ahead and keep studying like normal. Again, I do recommend reducing the number of new cards you study each day to something that’s really easy for you to manage; 4 new cards a day works well for me. You can do that from Options; scroll to the bottom and then set your Max New Cards.

Study Every Day

That’s pretty much it. However, you must study every day. If you miss even one day, you’ll notice immediately that you’ve started forgetting. If you’re really busy, you don’t have to study a new set of kanji (go to Options to turn new cards off) but you must review the kanji you’ve already studied. You must review every day without fail. Remember that this system is trying to be as efficient as possible. So, it offers you kanji to review just before you are likely to forget them. If you don’t review, you will forget. But, what if you really just don’t have the time today? What if, no matter what, you’re just not going to be able to find 25 minutes to review? In that case, read on.

+α

Once you’ve finished studying for the day, go to the Edit view and select all of the new cards you just studied. It might be a bit difficult to find them all depending on which direction they were swiped. It’s probably easiest to go to the Options screen first, turn off new cards and then turn one of the sorting options to Soon or Hard. That way, your newer, already studied cards will be sorted near the top of the Edit screen. On the Edit screen, use the Select option, and then tap all of the new cards you studied today to select them. After that, tap Done and then Export and then select Examples to Clipboard. If you study a lot of cards every day or have a ton of examples (again, about two per card is optimal), exporting examples could crash the app due to a lack of memory, so be careful. Don’t forget to turn the sorting option back off before your next study session so you can get a nice, random sort when you study again. Oh, and be sure to turn new cards back on, as well.

Go back to your lesson list and Create a New Lesson called something like RtK Reading. Go to the Edit tab and tap Import Cards. If you get a warning about dupes select Import New Cards. Go to Options and set the Study Style to Read. You can also set Kana Style to w/Eng if you want to have to tap less. I recommend you use this lesson to study whenever you have a free moment in the day: waiting in line, on the train, on the toilet or whatever; whenever you have a minute, pull this lesson out and study a few cards. Doing this isn’t as important as doing the actual RtK lesson, you have to do that one every day, religiously, so this one can just be for if you have extra time. Once you start getting quite a lot of cards, it’ll probably start saying you have 100 or 200 cards due each day. Don’t worry about that; just do as many as you can today and then sync and/smooth your study dates tomorrow. Seriously, don’t stress about doing this one every day; just consider it an optional booster. It’s also nice to have this to go through just in case you can’t find time to actually review your regular Remembering the Kanji lesson.

I think it’ll really reinforce your understanding if you have the chance to see your kanji being used in words in real sentences. You don’t need to be able to read the whole sentence, of course; there’re gonna be some kanji in there that you haven’t studied yet. Reading the sentence isn’t really the point. If you can read the sentence, great! Read it. If you’re worried about your pronunciation, copy the iSpeech girl (or guy, if you prefer). Her intonation is actually pretty natural most of the time. Slow her down and practice a couple of times. If you want to know what the sentence means use the hint button in the upper left. If there’s just a word you want to know, use the Analyze option (long press on the sentence) to analyze the sentence in imiwa? Like I said, reading the sentence isn’t really the point but that extra info and functionality is there to help if you need it.

Basically, you just want to get used to using the kanji in a realistic manner: seeing it surrounded by other kanji and being able to recognize it.

Final Words

What if there is a kanji you keep forgetting? That’s okay. There’s gonna be some tough kanji for everyone. You’ll probably run into kanji or words that you just can’t seem to remember, no matter what. I always forget how to say しつこい in English. I don’t know why; I just can’t seem to remember that word (it’s persistent, by the way). The best thing to do when you’re having some trouble is talk to someone about it. Hit up Kanji Koohii and their forums and see if anyone has any tips for you. If you still can’t seem to recall it successfully, just move on and don’t worry about it. Some kanji that you study later might give you some special insight that suddenly causes you to remember that kanji you were having trouble with. Really, it’s not a big deal. Japanese people forget kanji all the time. Just take it nice and easy, don’t create any unnecessary stress for yourself, and enjoy the journey.

Please don’t hesitate to contact me if you have any trouble or if anything here wasn’t clear. I’ll be more than happy to chat or Skype with you to help you get the most out of kanji Flow and your study time.